Palmer ‘Steampunk Guru’ Bruce Rosenbaum surrounds himself with his art and inspiration

Written and Photography By Patrick O’Connor

Palmer “Steampunk Guru” Bruce Rosenbaum lives among his inspiration where machine parts, antiques and other odds and ends wait in closets, on shelves and in drawers to be used.

In the converted Palmer church that is Bruce Rosenbaum’s home, gallery and workshop, an “aviator” in a Leonardo Da Vinci-like flying device, called Helioman, seems to hover over where parishioners once sat. As a kinetic, functional work of art, Helioman’s helicopter blades operate as a fan that cools the space.

Palmer “Steampunk Guru” Bruce Rosenbaum lives among his inspiration where machine parts, antiques and other odds and ends wait in closets, on shelves and in drawers to be used.

Bruce Rosenbaum’s art combines the old and new to create steampunk designs. Steampunk breathes life (or steam) into antiquated yet historically significant objects, refashioning them in new, exciting and “punk” ways.

Bruce Rosenbaum, who sees himself as a visionary, educator and project manager, organizes a team of artists and tradespeople to bring his ideas to life, like this “Shumachine,” inspired by the work of African American inventor Jan Matzeliger, who invented an early model of the Shoe Lasting Machine, which optimizes the amount of leather needed to make shoes.

Bruce Rosenbaum worked with a team of artists and tradespeople to recreate the work and lives of authors and inventors, like this skeleton face which is part of a reimagining of Mary Shelley’s “Frankenstein.”

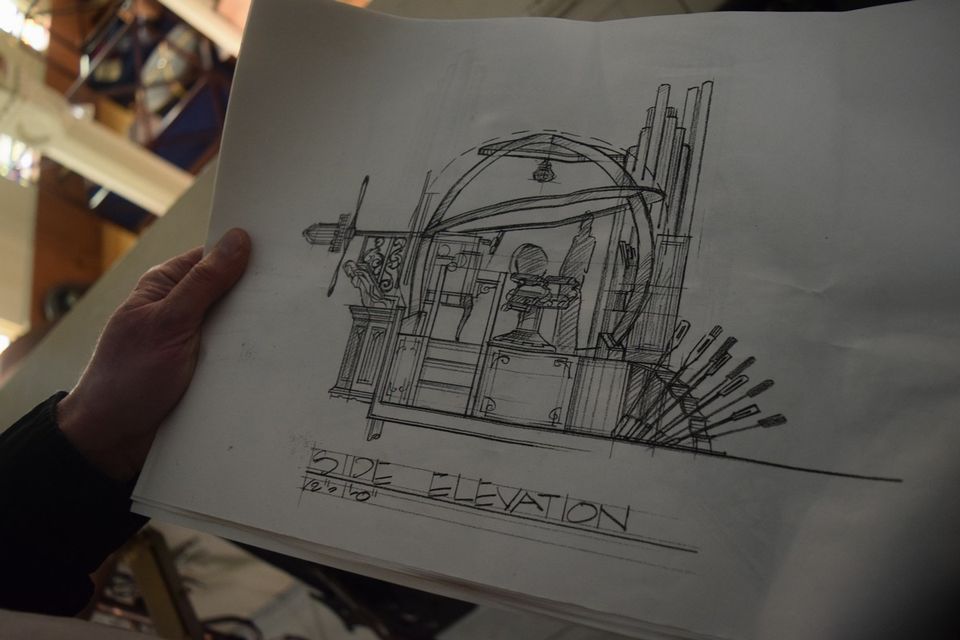

Plans for Bruce Rosenbaum’s office, which will be enclosed by the galvanized steel pipes of a 1902 Woodbury church organ and located in the choir loft of the former Palmer church that is his home, gallery and workshop.

A creature from one of Bruce Rosenbaum’s “humachines” is part of a reimagining of Jules Verne’s Victorian-era classic “20,000 Leagues under the Sea.” Rosenbaum worked with a team of artists and tradespeople to recreate the work and lives of other authors and inventors.

For Palmer steampunk master Bruce Rosenbaum, it’s all about adapting

I recently met Bruce Rosenbaum in his Gothic church in Palmer, which is his home, his gallery and his workshop. Walking through the converted church, which was built in 1876, we spent two hours talking about steampunk, rummaging through his strange inventory and checking out his even stranger creations.

After we said goodbye, I thought I had the makings of a great story, until I sat in my car and looked at my digital recorder, discovering that I had somehow deleted nearly the entire conversation.

I drove home in a daze, pulling into a parking lot to stare at my recorder, hoping the interview would magically reappear. When I got to my house in Holyoke, I emailed Rosenbaum, saying I’d understand if he couldn’t meet again. His response typifies his work as a steampunk artist. “We’ll adapt,” he wrote, ending with a smiling emoji.

Later, in a second interview, for which I used a pencil and notebook, Rosenbaum said, “If you start out with the attitude that things don’t always go your way, when you have adversity, you can calmly try to figure out another way.”

Named the “Steampunk Guru” by the Wall Street Journal and the “Steampunk Evangelist” by Wired magazine, Rosenbaum says one of the things that attracted him to steampunk was this focus on adapting: “To take one thing and turn it into something else.”

Coined in the 1980s, “steampunk” is all about reinvention, pulling together seemingly incompatible objects – often with a Victorian flair – from the past, and mixing them with the present to create something new for the future.

“It’s like a puzzle and the pieces are all around you,” Rosenbaum said. “You just need to put them together in a new way.”

With his design company, ModVic (which combines “modern” and “Victorian”) Rosenbaum sells and exhibits his fusions throughout the country. He’s been featured in The Boston Globe, The Chicago Tribune, The New York Times, CNN, Huffington Post, and National Public Radio, as well as on MTV, A&E, Discovery and HGTV. A single piece of his artwork sells anywhere from $5,000 to $1 million. He’s the person behind the mechanical whale sculpture in the lobby of the Nantucket Hotel & Resort.

And it all starts in the old church, which he shares with his wife, Melanie. Here, Rosenbaum lives among his creations, all in different stages of evolution.

Just outside of their bedroom, which was once the stage in the former church’s basement, hangs the steel frame of a “man” illuminated with vacuum tubes that can be dimmed or brightened with an antique stage lighting controller.

Upstairs in the gallery, a human-sized aviator in a Leonardo Da Vinci-like flying device seems to hover over where parishioners once sat. A fan that replicates a helicopter’s blades spins to cool the space on hot summer days.

Rosenbaum’s office, which is not yet finished, will be in the former choir loft, looking over the gallery. In the plans, a 1902 Woodbury church organ’s massive galvanized steel pipes enclose his desk, which is encircled by several orbiting rings. Picturing Rosenbaum in that space, he seems like a mad inventor. Yet, with his silver vests, smooth bald head, rimmed glasses and neatly trimmed goatee, he looks more like a magician. “In fact,” he said, “I worked as a magician for a while.” Still, when considering the collaboration involved in a single piece, the solitary magician doesn’t fit either. He’s more of a ringmaster. “I have to act as a ringmaster to pull so many people together.”

One project often includes a community of artists and trades people. “I need to work with others to make everything happen,” he said of the team of artists, engineers, welders, electricians and carpenters he employs. “The art forces me to work with others.”

Recently, they created “humachines” of iconic Victorian-era authors and inventors, including H.G. Wells, Mary Shelley and Thomas Edison, resurrected into odd contraptions that tell the story of their life and work.

Each piece is a sort of functional contradiction. “It’s all about opposites,” Rosenbaum said. “Art and science. Past and future. Form and function. Man and machine.”

Divergent thinking like this helps him create, he said.

“And thinking in opposites opens your mind for solving problems in your own life,” he added.

To bring these lessons to others, Rosenbaum is working with a committee of educators, business people, town officials and artists to create a steampunk “makers-space” in Palmer, where people would have the tools and machinery needed to create their own work. “And you would have teachers there, too,” he said. “People who can guide you.”

Rosenbaum is also working with area schools to create a program where high school students can work on steampunk projects, combining STEM skills with the trades, like welding, woodwork and electronics, as well as with art. As part of this, he wants to team up with the annual Brimfield Antique Shows (which begin the first of three week-long fairs this year on May 8.) “Students would go to Brimfield and find objects, and then for a year they would build. Then we would showcase their work,” he said.

The committee is also planning a steampunk festival and makers fair, where people can see and make steampunk art.

Yet, for Rosenbaum, what matters is not just the thing made. “For me, the meaning and what steampunk can do is much deeper than that,” he says.

It’s the process, according to Rosenbaum, that combines creativity, problem solving, collaboration and the ability to adapt, in life and art: “My greater mission is to teach people about this.”